Communication strategies driving online health community patient awareness and engagement investigated within atrial fibrillation context

Literature review

An overview of the literature is first provided to define the communication variables, before detailing the design of the online field experiment with its multiple communication concept variations. The review begins with an exploration of developments within OHCs, followed by insights from health and marketing communication literature. It then covers empirical work on the influence of emotions, topics, appeal, and linguistic style on (health) behavior. This comprehensive literature review served as the foundation for the development of the communication concepts and the design of the concept landing pages. Table 5 provides a summary of the literature review, outlining the communication elements and patient journey stages that informed the experimental setup.

Digital healthcare platforms & communities

OHCs are considered as “a special type of online social network in which members interact in health- or wellness-related virtual communities to seek information, help, emotional support, and communication opportunities”12. OHCs fulfill demands of health consumers who are unable to obtain all information they need from traditional health care providers. Health consumers typically aim to find peer-to-peer support, trustworthy information on advances within a specific health field or companions with “lived experience” of a particular health condition and its treatments. Platforms such as My Health Team offer chronically ill individuals social networks where they can interact with other companions on disease symptoms, management, and treatment while also learning more about their condition through availability of trusted information. Other than traditional communication lines, which include doctor-patient-interactions, direct-to-consumer marketing, and hospital-to-consumer marketing, patients nowadays interact with companions, caregivers, and other professionals directly1. This results in new information streams of which peer-to-peer influence (e.g., patients Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM)) and patient co-creation (e.g., patient and hospital collaboration on treatment processes) are common examples. Especially the latter may result in valuable outcomes as patients contribute to health service innovation and participate in research. A study done by Hodgkin et al.3 highlighted four ways OHCs create value, namely by (1) offering patients and caregivers new resources in the form of support, information, and solidarity, (2) providing non-patients with new insights, (3) challenging power dynamics between patients and health professionals, and (4) growing knowledge through data collection. Patients nowadays are more empowered, potentially offering incredible value to the health field when utilized correctly by all stakeholders involved.

Marketing and communication in digital health care management

Starting an OHC can be challenging, and these platforms have not been widely adopted yet2. As such, previous studies brought insights into which factors drive participation of members. The role of platform values and characteristics in platform adoption and engagement have priorly been investigated in particular. Multiple studies found that social support, relationship commitment, and an ethical and trusting environment are crucial for OHCs to grow engaging communities and produce value10,45,46. Unlike research on value creation and quantification of OHCs, knowledge on OHC marketing and communication approaches is less developed. Besides one study showing that Facebook is an effective platform for OHC membership promotion31 and another study which demonstrated that fear can result in perceived threat and may evoke cyberchondria, while coping appeals resulted in higher efficacy and impulsive purchasing behavior in OHCs47, research on marketing and communication approaches for OHC promotion remains scarce. Thus far, research in health marketing and communication is specifically fixated on business-to-business (B2B) and DTC advertising strategies1. More importantly, as previously mentioned, these practices are only partially understood. Existing work has incorporated multiple marketing and communication angles that potentially influence health attention behavior in the field of DTC. A widely studied segment is the influence of emotion on health behavior15,17,18,19,20,21,48, showing varying results. For instance, Carey & Sarma20, show that fearful and efficacy messages can positively affect driving behavior, while others found that loving and coping content activated individuals in charity and OHC purchasing contexts47,48. Besides, Kim et al.19 show that both love and fear inducing messages can benefit health behavior. Like in the field of emotion and health behavior, contradicting findings have been found in other marketing and communication fields as well. For example, message narratives have been studied in the form of information source narratives, such as expert statements versus patient or celebrity statements18,22,23,28. Keller & Lehmann18 conclude from their meta-analysis that patient testimonials stimulate health behavior while Hsu23 and Jebarajakirthy et al.28 found that the expert narrative positively influenced health behavior. However, Emmers-Sommer & Téran22 found that individuals tend to respond better to celebrity endorsements. Additionally, multiple authors have investigated the role of narratives within linguistic style and message appeal and also show different findings15,18,20,24,27,48,49,50. Carey & Sarma20 found that persuasive messages positively influence driving behavior, especially in the short term. However, Lütjens et al.50 uncovered that informative messages positively impact the attitude towards online advertising. Mixed findings were found in linguistic features on health behavior too. Chen & Bell27 state that a first-person linguistic narrative enhances the persuasiveness of a health message, however, their meta-analysis showed that this did not necessarily result in desired health behavior of the participants. Besides, Keller & Lehmann18 concluded that directly targeted messaging may yield positive health behavior outcomes in low involvement audiences, but that general messages were more effective in high involved audiences. These studies show different effects of communication variables on health behavior for diverse audiences which results in varying outcomes and recommendations. These outcomes make it challenging for health communication managers to choose appropriate marketing and communication strategies in practice.

It has become evident that previous work in the field of marketing and communication in OHCs is limited. Additionally, many studies rely on surveys, making it difficult to measure human behavior across various customer journey phases, such as impression and click behavior in the awareness phase, average time on page or sign-ups in the engagement phase, or information sharing and return rate in the activation and loyalty phase. Another crucial aspect missing is the consideration of the underlying evolutionary motives driving our behavior. Griskevicius & Kenrick35 outlined seven fundamental motives that underlie all human behavior, which may help to understand how these motives influence health behavior and inform marketing and communication strategies for OHC promotion. Moreover, previous research has primarily examined marketing and communication elements in isolation. Health marketers and managers could benefit from understanding the combined effects of these elements to create a greater impact in the field. Therefore, comprehending how these elements raise awareness of OHCs and drive engagement on the platforms can provide insights into when and how they are most effective.

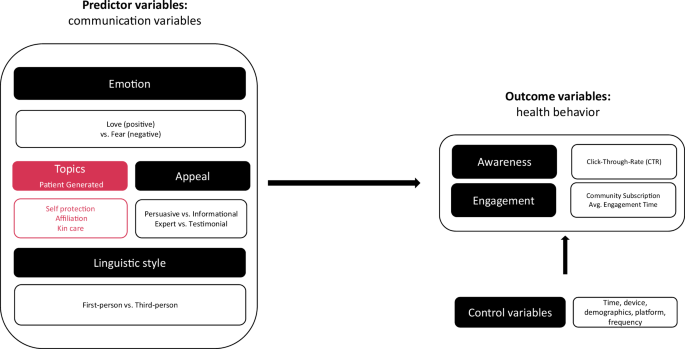

Conceptual framework & components of the model

Before further elaborating on the marketing and communication elements that we include in our online field research, we first shed light our conceptual model. We investigate the influence of marketing and communication elements on patient’s awareness (i.e., CTR) of the OHC that is included in our study. Moreover, we investigate the effect of these communication elements on the engagement (i.e., community subscriptions and average engagement time) of patients in the OHC on AF.

Based on the existing literature, communication variables represent opposites of one another. For emotion, love and fear are included as these emotions are prominently studied. Additionally, considering that self-protection, affiliation, and kin care as evolutionary motives for human behavior are relevant to OHC, these have been selected into the framework. For message appeal we compare patient narratives (i.e., testimonial) against expert narratives and informative messaging against persuasive messaging. Finally, we include linguistic style in which we compare a first-person narrative with a third-person narrative.

It’s important to draw attention to the control variables of this field experiment. Considering the nature of our data and context, we include moments in time, device category, demographics (i.e., age and gender), platform (i.e., Facebook and Instagram), and ad exposure frequency as control variables in our framework.

Model components

Prior research in health marketing and communication primarily focuses on emotional appeals and diverse message framing strategies. These elements are defined before reviewing the literature on the specific marketing and communication components.

First of all, emotion can be described as “valenced responses to relevant stimuli that are directed toward specific targets (e.g., people, objects, or events), differentiated, and relatively short-lasting”51. Within the health marketing field, emotion has especially been applied to generate threatful, fearful or on the contrary, hopeful, coping, and loving messages. Second, message appeal is defined as the type of request conveyed by a message. In this study, expert and patient (i.e., testimonial) narratives are employed to communicate informational as well as persuasive appeals. Finally, we include linguistic style in our model which can be distinguished between linguistic content (i.e., nouns, verbs, adjectives that carry the content of a communication) and linguistic style (i.e., prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs which represent sentential meaning and style)52. Since the study centers on first-person and third-person communication perspectives, the emphasis is placed on the linguistic content rather than the stylistic features of language.

Fundamental motives of human behavior

The inclusion of the evolutionary human motives in the field of health behavior is relatively new and findings are scarce. Graham & Martin53 stress that studies on the effect of marketing communication variables on health behavior only partly explain why behavior occurs as in reality health behavior is often sudden, unexpected, and non-linear. Therefore, little is known about how marketing communication influence behavior. To improve our understanding of drivers of health behavior, we must consider the underlying motives for human motivations. Maslow’s classic hierarchy of needs that originally consists of (1) immediate physiological needs, (2) safety, (3) love, (4) esteem, and (5) self-actualization was modified by Kenrick et al.54 based on developments in the field of evolutionary biology, psychology, and anthropology which showed that mating and reproduction influence our motivation. Their updated hierarchy of fundamental human motives include (1) immediate physiological needs (self-protection), (2) self-protection (disease avoidance), (3) affiliation, (4) status/esteem, (5) mate acquisition, (6) mate retention, and (7) parenting (kin care).

Prior to elaborating on the activation cues underlying human behavior, it should be acknowledged that not all fundamental human motives are directly applicable to the context of OHCs. For example, individuals that are motivated by status, which is characterized by seeking products to signal prestige, will most likely not sign up to OHCs to fulfill this need. As a result, the motives and concerns of patients with AF were analyzed to refine and select the most relevant fundamental motives for inclusion in this study (see Supplementary Reference 1). The majority of outcomes are directly in line with self-protection, affiliation, and kin care. Patients specifically mention that they are concerned with their heath and therefore seek to understand how to live with AF, which fits the motive of self-protection. Some others find it important to share thoughts and experiences with other patients and want a feeling of belonging, which fits with affiliation. Finally, there is also a group that state that AF interferes with family care and that they are concerned their children may develop AF as well, which fits with kin care. Therefore self-protection, affiliation, and kin care have been included in this study’s framework as patient-generated topics.

Each evolutionary motive can be activated through triggers and will result in specific behavior. Griskevicius & Kenrick35 reviewed the triggers, behavioral outcomes, and cues that activate fundamental motives and their associated behavioral tendencies. Overall, they found that self-protection (i.e., avoiding danger) is triggered by angry faces, darkness or loud noises, and threatening persons. Self-protection results in ‘increased tendency to conform’, ‘decreased risk-seeking’, and ‘increased aversion to losses’. Affiliation is activated by friendship-related threats or opportunities, leading to behaviors such as seeking socially connective products, relying on word-of-mouth, and consulting reviews for others’ opinions. Finally, kin care is triggered by visualization of family or vulnerable others and results ‘increased trust of others’, ‘increased nurturance’, and ‘increased giving without expectation of reciprocation’.

As briefly mentioned before, the implementation of evolutionary fundamental motives of human behavior (besides disease avoidance) in health behavior research remains scarce. Besides Okuhara et al.37 that demonstrated that kin care motives are just as effective as disease avoidance motives in generating a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine in Japan, studies on fundamental human motives in combination with other marketing communication elements are lacking.

Emotions: love and fear

Within the extant literature, the concepts of love and hope have been used within different contexts. Within the domain of marketing research, the term ‘love’ has been described as ‘emotions of compassion and desire’15. Just like Cavanaugh et al.15, this study does not address the emotion of love as romance. Instead, love encompasses fondness and genuine care for oneself as well as important individuals in one’s life (e.g., caregivers, family or friends).This study frames the emotion ‘love’ positively, based on evidence that positive emotional content increases message virality16,55 and attention of individuals17. Love is paired with hope in this study to make love a positive emotion. Hope is often defined as the anticipation of a favorable outcome in the future, providing a sense of motivation that one’s efforts can yield positive results and can shape how both individuals and others perceive hurdles56. Besides, Wrobleski & Snyder36 researched the role of hope and health outcomes in elderly people. One of their findings indicates that individuals with high levels of hope exhibit greater self-efficacy (defined as confidence in achieving goals) and show more engagement throughout the goal pursuit process compared to those with lower levels of hope.

Another commonly studied field within the health marketing literature is the emotion fear. Back in the 1950s, the belief was that fear evoking campaigns would result in desired health behavior of individuals57. Later, in the 1960s, researchers found inconsistent findings on the use of threat-appeal on health behavior which drove Higbee’s57 attempt to investigate variables that may interact with fear to make it less or more effective in health communication. Some of his findings show that (1) threat is superior to low threat in persuasion, (2) the specificness and ease of implementation of recommendations increases the effectiveness of fear, even more so than for efficacy, and (3) responses of fear differ among individuals where individuals with chronic anxiety seem to respond best to fear framing. The author also stresses that evidence on interest in fear messaging was inconsistent. Recent studies shed more light on the effectiveness of fear as the digitalization of content and health advertisements allowed academics to investigate online behavior after exposure with fearful messaging. Forbes et al.21 demonstrated in their fearful animal imaging experiment that fear triggers fundamental human instincts and facilitates rapid processing with minimal stimulus information which raises attention. In a recent study by Berger et al.17 the same effect was witnessed. The authors showed that anxiety, but also hope and excitement capture attention. Moreover, these results also seem to be valid in the virality of messages as both positive and negative laden messages seem to increase virality of a message16,55,58. Many findings on health behavior of individuals after health message exposure are in line with previous findings from Higbee57. For instance, Carey & Sarma20 found that fear in combination with efficacy in messaging significantly lowers driving speed of young male drivers. However, fear alone did not make an impact. Later, Ort & Fahr48 found similar results and confirmed that threat alone did not influence health behavior towards Ebola vaccination and that efficacy must be used in combination with threat to affect an individual’s attitude towards the vaccine. Fu et al.47, investigated the dynamics which determine success and failure of fearful messages and found that fearful messaging can result in cyberchondria. This means that individuals exposed to threatful content, may psychologically distance themselves from the message sender which may result in undesired health behavior. Both love and fear can result in either PFC or EFC coping strategies47. Where a PFC approach results in problem solving and an individual taking direct action, the EFC approach holds the opposite and makes threats perceived as less severe which in turn results in psychological distancing, wishful thinking, and denial. Considering the previous work on the emotion love and fear, it is expected that both the emotions of love and fear can positively influence patients’ awareness of OHCs and their engagement with the platform.

Appeal: expert and testimonial appeal

The influence of message narratives, particularly those coming from patients, experts, or celebrities, on health behavior have been previously investigated by scholars. Various studies have examined the effectiveness of different narrative sources in promoting health-related behaviors and attitudes. As such, Keller & Lehmann18 conducted a meta-analysis based on 60 studies, examining the impact of patient testimonials on health behavior. They concluded that case information (e.g., patient testimonials) stimulate health behavior, suggesting that narratives from individuals who have personal experience with a health issue can be effective in promoting behavior change. Furthermore, like previously mentioned, both Hsu23 and Jebarajakirthy et al.28, found that expert narratives positively influenced health behavior. Experts, such as healthcare professionals or researchers, are often perceived as credible sources of information, and their narratives may carry more weight in influencing health behavior. Besides work done on expert and patient narratives in health messaging, Emmers-Sommer & Terán22 explored the role of celebrity endorsements in health communication. They found that individuals tend to respond better to celebrity endorsements compared to other types of endorsements. However, it’s worth noting that while celebrities may be perceived as credible, consumers may not necessarily trust them as the only advocates for health issues. Previous work suggests that both patient testimonials and expert narratives can effectively influence health behavior, although in different ways. Patient testimonials may appeal to individuals on a more personal level, drawing from shared experiences and emotions, while expert narratives may provide authoritative and evidence-based information. However, it is unclear which of these narratives is more effective in generating awareness for OHCs and engagement of patients on these types of platforms. Considering the fact that Keller & Lehmann18 recommend strong source credibility to influence health behaviors among low-involvement audiences, it can be argued that expert narratives are more effective in enhancing awareness and engagement among newly reached audiences.

Appeal: informative and persuasive

In addition to the source of the message, the nature of the message itself is also considered a key component of its appeal.Within the health communication domain, authors used persuasive versus informative information in health messaging to influence health behavior, with studies exploring the effectiveness of different message types in driving health behavior. In this health context, we perceive informative information as factual information and persuasive information as an opinion or experience. Carey & Sarma20, conducted research on the impact of persuasive messages on driving behavior. They found that persuasive messages positively influenced driving behavior, particularly in the short term, suggesting that messages designed to persuade individuals to engage in specific behaviors can be effective in stimulating immediate action. In contrast, other work showed that informative messages positively influenced attitudes towards online advertising and can enhance perceived brand authenticity in the context of warm and competent brands49,50. These findings indicate that messages containing factual information can be effective in shaping perceptions and attitudes as well. However, Fu et al.47, noted that persuasive messages were perceived as counterproductive by marketers as they can potentially cause brand aversion. Whether this is also the case within the field of OHCs is unknown. Drawing upon the effectiveness of the emphasis of credibility in low audiences, we assume informative messaging will be more effective in generating awareness of and engagement in OHCs.

Linguistic style: first-person and third-person linguistic style

As previously mentioned, this study focuses on the linguistic content of messaging. This approach involves primarily using specific nouns, verbs, and adjectives to construct the message content in either a first-person or third-person narrative. There have been previous studies that considered the impact of first-person versus third-person linguistic style in health messaging on health behavior outcomes. Chen and Bell27 conducted research on the compelling nature of first-person linguistic narratives in health messaging. They found that first-person linguistic narratives enhanced the convincing power of health messages. However, their meta-analysis revealed that this did not necessarily result in desired health behavior changes among participants. This suggests that while first-person narratives may be effective in capturing attention and generating interest, they may not always lead to actual behavior change. In contrast, Keller & Lehmann18 concluded that directly targeted messaging may yield positive health behavior outcomes in low involvement audiences, but general messages were more effective in high involvement audiences. Their finding indicates that the effectiveness of linguistic style in health messaging may depend on the level of audience involvement and engagement with the message content. Considering these findings, we expect that a first-person narrative may be more effective in generating awareness, but that a third-person narrative is more effective in engagement of individuals in OHCs.

Designing the communication concepts

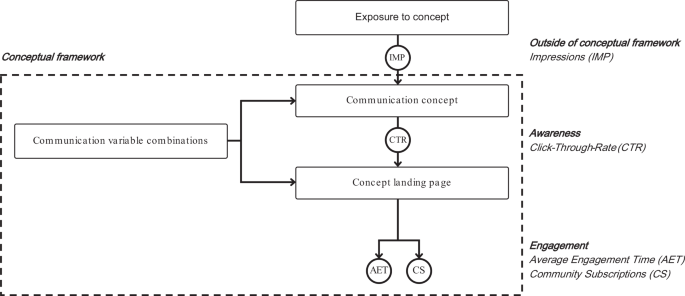

We designed and performed an online field experiment, namely a quasi-randomized study conducted in a real-world setting, that captures the online behavior of individuals after being exposed to various health related communication on AF. This online field experiment resulted in three datasets from Facebook, Instagram and the AF OHC website. On this website, members (i.e., patients and other stakeholders) can share experiences and insights on AF with the aim of co-creating new research pathways together with other patients and stakeholders on AF treatment and prevention. The dataset coming from Facebook and Instagram consists of 795,812 unique users that were reached, and the OHC dataset covers 18,426 website visitors in the Netherlands. Similar to the study conducted by Fritz et al.32 the online field experiment allowed us to measure individuals’ real-time behavior across multiple platforms. Therefore, the experiment is suitable to investigate not only the behavior of users towards health communication concepts upon the first encounter with the ad, but also the level of engagement after clicking. In total 12 communication concepts consisting of different combinations of communication elements (Table 6) were designed based on variable definitions from previous work on (health) behavior (Table 5) and AF patient experiences that were collected by the AFIP foundation (see Supplementary Table 1). Like Cavanaugh et al. and Fritz et al.15,32 we expressed communication elements through images and text while incorporating contexts of interest that were raised by AF patients. We then pre-tested the concepts (Supplementary Reference 3). The communication concepts are developed in collaboration with an in-kind contributing digital marketing agency with expertise in copywriting, website design and social advertising. After pre-testing, the final communication concepts were launched on Facebook and Instagram through paid advertising in the Netherlands. Figure 2 displays the structure of the online field experiment. For each communication concept, we developed a matching website landing page in the OHC of the AFIP foundation which included the same visual and similar textual elements as were displayed in the communication concept. Keeping in mind that self-efficacy is needed for individuals to act after processing health messages16, we included the message that something can be done about the situation in every communication concept and its’ matching landing page (Supplementary Reference 2).

In total, 12 different combinations (Table 6) of communication variables from the conceptual model (Fig. 1) fueled the communication concepts and concept landing pages on the website of the OHC. The online field experiment is conducted on Facebook and Instagram, where communication concepts are exposed to users, measured as impressions (IMP) which are not part of the conceptual model. The Click-Through Rate (CTR) of these concepts serves as a measure of awareness. After clicking on a concept, individuals are directed to the concept landing page of the OHC. During their visits to the OHC, Average Engagement Time (AET) and Community Subscription (CS) are tracked as indicators of user engagement. This design enables a comparison of how different communication elements impact both awareness and engagement.

Pre-testing the communication concepts

In April 2023, a pre-test was conducted among 165 atrial fibrillation (AF) patients to evaluate whether 12 communication concepts effectively reflected the intended communication variables. After removing incomplete responses, 118 participants remained. A digital marketing agency created two variations for each concept (e.g., 1.1 and 1.2), differing slightly in imagery and text. Participants were randomly shown two Facebook-style ads and asked to rate each using a matrix of 5-point Likert scales measuring emotional and content elements (e.g., “Terrifying,” “Loving,” “Representing expertise”). Following the approach of Cavanaugh et al.15, the highest-rated variation per concept was selected for the final experiment design. For instance, concept 2.1 (score: 20.4) was chosen over 2.2 (score: 17.9). Per concept, average ratings and standard deviations were documented. Based on these results, four concepts (i.e., 1, 3, 5, and 12) were revised to better align with the intended variables, using the framework of fundamental human motives by Griskevicius and Kenrick35. Supplementary Reference 3 provides the pre-test results.

The data and metrics

The online field experiment conducted in the Netherlands with an AF population target of at least 380 thousand patients in a time range of one month (May 23, 2023, until June 23, 2023). However, everyone above 18 years old was targeted to reach as many individuals as possible for a higher probability of substantial exposure of the communication concepts among caregivers and family members of patients. In total 795,812 unique Facebook and Instagram users were reached. The Facebook and Instagram dataset includes information on the online behaviors of users visiting these platforms while also providing demographic characteristics of the users which are self-reported of nature. As previously mentioned, CTR was measured as a signal of awareness. The OHC of the AFIP foundation on the other hand provided data on the user behavior that occurred on the website. Engagement of users was measured in two manners. First, average engagement time was measured with the premise that the more someone pays attention, the more someone learns about the subject59. Average engagement time is defined by Google as “the total length of time your website was in focus or your app was in the foreground across all sessions/the total number of active users” (Google, 2025, Second, community subscriptions served as a measure of engagement, which was defined as the number of users that signed up to become a part of the community through a sign-up form that was provided on the website landing page.

A quasi-randomized design

While Meta provides an A/B testing framework that claims random ad delivery across conditions, recent research60 highlights the potential influence of platform-level optimization algorithms that adaptively adjust ad delivery to maximize engagement. Therefore, we do not claim strict randomization in the traditional RCT sense but rather followed a quasi-randomized design. Similar to Chopra et al.61, who describe their study as quasi-randomized due to staggered, externally imposed conditions at the cluster level, our ad campaigns were subject to stochastic delivery within fixed budgets and gender targeting. This quasi-randomized structure aims to create sufficient variation to estimate treatment effects under real-world conditions, particularly when also controlling for key covariates. To mitigate delivery bias and approximate random allocation as closely as possible within platform constraints, we: (1) structured campaigns with equal budgets and gender-based segmentation, (2) launched campaigns simultaneously to avoid time-based delivery bias, and (3) included key covariates (i.e., age, gender, device type, and time of day) as control variables in all regression analyses to account for potential confounding. Additionally, we included key demographic and contextual variables (age, gender, device type, platform, exposure frequency and time of day) as covariates in the regression models to control for potential confounding. Quasi-experimental online field experiments balance ecological validity with reasonable internal validity. As noted by Boegershausen et al.60 such designs are particularly useful for testing whether theoretically grounded interventions retain their effectiveness when deployed in real-world settings. While not suited for pure causal inference or theory testing, this approach allows for robust assessment of communication effectiveness under naturalistic conditions. Meta conducted the allocation of our communication concepts, targeting users aged 18 and older. To balance exposure between genders, we used restriction methods, splitting the experiment and managing the budget for men and women. Moreover, Meta’s auction system ranked communication concepts by a total value score, including bid amount, estimated user engagement, and quality of the communication concept. Their models predicted which concept each user was most likely to interact with based on behaviors on and off Facebook. Users were then directed to a specific concept landing page. Additionally, allocation concealment was ensured by Meta’s automated processes, preventing us and participants from influencing the assignment to the communication concepts. In the end, the sequence generation, enrollment, and assignment were fully managed by Meta. Anonymized data was accessed after finalization of the experiment, allowing for a blinded analysis. Facebook and Instagram served solely as distribution platforms and had no other role within the online field experiment.

Data analysis

To ensure enough power for this study, the online field experiment ran until each communication concept received at least 1000 visitors (i.e., participants the clicked on the communication concept) for its landing page. Everyone who interacted with the communication concepts were included in the study. By utilizing Python 3.10.12 Statsmodel and SPSS 29.0 linear regression models were trained, estimating the impact of communication elements on awareness and engagement metrics, namely CTR and average engagement time. Additionally, logistic regression was used to assess the effects on community subscriptions. A stepwise approach was used, starting with a basic model of the main communication elements’ effects on the outcome variables. More complete models were then iteratively constructed, incorporating control and interaction variables to examine their differential impact. This resulted in four models for engagement outcomes: the first assessing predictor variables, the second examining control variables, the third combining both, and the fourth including all variables and their interactions. For CTR, we constructed three models without interaction variables. The main models are based on engagement data (i.e., average engagement time and community subscriptions) of the OHC and is individual level of nature. Time (i.e., weekday vs. weekend, day vs. evening and work hours vs. non work hours) and device (i.e., mobile, desktop and tablet) were included as our control variables. Additionally, two supportive models based on the aggregated CTR performances of our communication concepts from Facebook and Instagram data were developed, to verify if the effects observed in the engagement model also hold in the awareness context. The analysis was divided into two parts: the first controlled for age, gender, and exposure frequency, while the second controlled for platform, device, and exposure frequency. There was no data monitoring committee. Supplementary Table 3 displays an overview of the variables used in our models.

Ethical approval and GDPR compliance

The research was approved by the Economics and Business Ethics Committee (EBEC) at the University of Amsterdam under reference number EB-9521. Participants accessing the AFIP foundation website provided informed consent prior to participation. For the advertisements conducted on Facebook, user engagement falls under the platform’s data use policy. All visuals used in the advertisements and on the AFIP foundation’s website were selected from the licensed Adobe stock image library. These images were chosen by the researchers and designers of the in-kind contributing agency and do not represent real patients, making additional consent unrequired. No personally identifiable information (PII) was collected at any stage of the study. The awareness dataset used in this study was established using aggregated and anonymized advertising performance data from Meta platforms (Facebook and Instagram). This dataset was generated within Meta’s Ads Manager, which provides summary-level (i.e., aggregated) metrics (e.g., impressions, click-through-rates, and reach) without any access to user-level data. The dataset does not contain personal data as defined under the GDPR, and is therefore not subject to its provisions (Recitals 26 EU GDPR, 2025, Meta’s advertising tools function under the platform’s Terms of Service, to which users implicitly consent by creating and maintaining an account. For website behavior, we relied on pseudo anonymized data from Google Analytics 4 (GA4), which uses user_pseudo_ids rather than personal identifiers. To comply with GDPR, the OHC takes measures which include (1) obtaining explicit user consent for the use of analytics data for statistical and research purposes, (2) configuring GA4 with privacy-preserving settings, including the deactivation of Google Signals, (3) entering into a data processing agreement with Google in accordance with Article 28 of the GDPR (Art. 28 GDPR, and (4) applying strict organizational and technical controls to restrict access to GA4 data to authorized personnel only. Moreover, to improve transparency following the review process, a debrief page was published (Supplementary Reference 6) after the campaign concluded. This page outlines the purpose of the study, the nature of the data collected, and how privacy safeguards were upheld.

link