Participant characteristics

Initially, 12 eligible young adults (6 men and 6 women) and 12 eligible older adults (6 men and 6 women) were successfully recruited and interviewed based on the inclusion criteria. Although the data collected from the 12 young adults initially appeared to achieve theoretical saturation (as no new theoretical insights or themes emerged), 2 participants later withdrew from the study. They expressed concerns that some perspectives shared during the interviews were sensitive (e.g. related to stigma surrounding long COVID in China), from their point of view, and felt it would be inappropriate to include their data in the study. Despite their withdrawal, theoretical saturation was still maintained. However, to ensure theoretical saturation among older adults, one additional participant was recruited and interviewed to address concerns that certain aspects of holistic care expectations may not have been fully captured in previous interviews. This ultimately confirmed saturation in the analysis. As a result, the whole analysis process included data from 10 young adults and 13 older adults. The average interview duration was 39.1 min for young adults (range, 31–55 min) and 37.5 min for older adults (range, 30–57 min), with an overall average of 38.2 min. The mean age was 31.2 years for young adults (range, 25–37 years, standard deviation = 4.0) and 70.8 years for older adults (range, 61–78 years, SD = 4.7). Although physician-confirmed cases were targeted during recruitment, none were identified, as all participants reported their cognitive impairments based on self-perception only. This outcome might reflect the current context in China, where limited awareness among healthcare providers and the absence of established diagnostic guidelines have meant that formal diagnoses remain rare. Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the 23 participants included in the analysis.

Characteristics of cognitive symptoms reported by participants

All participants included in the final analysis (N = 23) reported experiencing long COVID-associated cognitive symptoms based solely on subjective self-perception rather than formal diagnosis in hospital or primary care settings (Table 1). All participants denied any prior noticeable cognitive impairments before contracting COVID-19, attributing their symptoms solely to post-COVID-19 effects in their own perspectives, as confirmed during interviews. These cognitive symptoms did not always noticeably manifest after the initial infection; in several cases, they appeared following two or more reinfections.

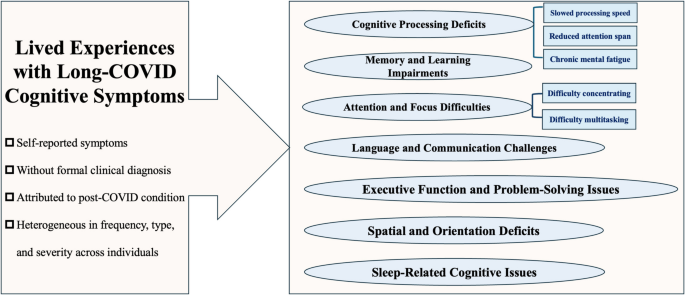

Figure 1 illustrates the spectrum of cognitive symptoms reported by participants during interviews. These included but were not limited to memory impairment, difficulty concentrating, word-finding challenges, slowed processing speed, reduced attention span, impaired problem-solving skills, difficulty multitasking, confusion or disorientation, poor executive function (e.g. complaining about leaving food unattended as a result of losing track of time), challenges in learning new information, spatial awareness deficits (e.g. complaining about having trouble following maps, even though they were previously familiar), chronic mental fatigue. The presentation of these symptoms varied widely in frequency, type, format, and severity among individuals. Additionally, we noticed that some participants reported that sleep disturbances (e.g. insomnia or disrupted sleep patterns) could significantly trigger or worsen their cognitive issues, and that their cognition improved once their sleep quality improved. While the types of symptoms reported were broadly similar across young and older adults, with no consistent age-specific themes emerging at the group level, differences in perceived severity and frequency were visible between individuals of different ages. For transparency, an anonymised and age-stratified summary of participants’ self-reported symptoms, including perceived severity, frequency, and sleep-related issues, is provided in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Spectrum of core cognitive symptoms reported by participants

In this cohort, memory impairments were among the most frequently reported symptoms in both young and older adults, primarily affecting short-term memory functions such as short-term prospective and episodic memory impairments. Participants commonly described difficulties recalling the location of personal items or remembering planned activities from recent days or hours. Sleep disturbances, particularly insomnia, were frequently cited as exacerbating these memory issues. Other commonly reported symptoms included impaired executive function in daily tasks (e.g. difficulty with meal preparation, which requires planning, organization, and multitasking), chronic mental fatigue (e.g. feeling mentally drained after routine activities like grocery shopping or attending a meeting), and verbal communication challenges (e.g. reduced verbal fluency, difficulty recalling words, and disorganised speech).

Past management experiences with long COVID-associated cognitive symptoms

The past experiences of managing long COVID-associated cognitive symptoms, including the strategies used to manage these symptoms and participants’ perceptions of their effectiveness, differed remarkably between young and older adults in this study (Fig. 2). Among young adults, over 50% of participants with symptoms did not visit a primary care provider or seek other forms of external medical care. This was often due to a subjective perception that the symptoms, though bothersome, were largely tolerable and manageable without professional intervention. Practical strategies were commonly employed, such as using tools like to-do lists or alarm clocks to aid memory. One participant described this approach: “If there’s something important, I can use a memo to write it down, or I need an alarm clock to remind me so that I don’t forget” (woman, 30 s). In addition, several participants emphasised psychological adaptation, adopting an attitude of acceptance and adjustment, particularly when the symptoms did not severely disrupt their overall functioning. Some also emphasised the important role of self-managing sleep and maintaining good sleep in supporting cognitive improvement.

Past frequently used strategies for managing long COVID-associated cognitive symptoms by age group

For a few young adults, however, cognitive symptoms such as memory impairment were more pronounced, remarkably affecting daily life and, in certain cases, academic performance. Despite trying practical strategies, these participants reported difficulty finding effective approaches to address these challenges. One participant shared how these symptoms impacted their studies: “I’m studying [participant’s major] subject, which involves a lot of memorizations. I just can’t get that information to stick in my mind anymore. Revising has become incredibly difficult” (man, 20 s).

Older adults, on the other hand, reported distinctly different approaches to managing their symptoms. Family support played an indispensable role, with many relying on relatives to help them remember daily tasks, such as taking medication or carrying essential items. For example: “If I need to grab something later, I often forget, but my wife always reminds me” (man, 60 s). Participants also reported using environmental cues, such as placing items in visible locations, or maintaining consistent daily habits to reduce the impact of forgetfulness. For some, improving sleep was an important strategy, achieved through sleep aids or Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which they believed indirectly improved cognitive symptoms. For example: “Taking medicine to regulate sleep helps. When my sleep improves, my memory is better” (woman, 60 s). Maintaining social interactions, such as brief conversations with family/community members or going for walks, was also cited as a way to stay mentally active.

Comparison of treatment preferences and expectations between young and older adults

The treatment preferences and expectations of young and older adults in managing long COVID-associated cognitive symptoms revealed distinct patterns. Among young adults, a central theme was a “preference for non-pharmacological interventions” (Fig. 3a), comprising two subthemes: “self-directed approaches” and “emotional and psychological support”. In contrast, the central theme for older adults was a “balanced use of pharmacological interventions” (Fig. 3b), comprising three subthemes: “non-pharmacological interventions”, “holistic expectations”, and “medication for cognitive symptom management”.

Thematic and conceptual map of age-specific preferences and expectations

For young adults, the first subtheme, “self-directed approaches”, includes four major concepts: practical tools (e.g. to-do lists and alarms), self-management of sleep, psychological adaptation, and physical activity/exercise. Many young participants in this study expressed an expectation of minimal reliance on formal medical care, preferring self-directed strategies, particularly practical tools such as to-do lists, alarms, and digital reminders to manage memory-related issues. These tools were viewed as essential for maintaining productivity and managing daily tasks. However, exceptions were noted among those who still expected to receive formal medical care, particularly when they perceived these self-directed approaches as offering minimal or negligible benefit.

Self-management of sleep emerged as a critical concept in managing cognitive challenges among young adults, with disrupted sleep perceived both as a symptom in itself and as a factor exacerbating existing cognitive symptoms. Young adult participants described efforts to improve sleep quality through behavioural adjustments, including maintaining consistent sleep schedules, practicing relaxation techniques, and avoiding stimulants before bedtime. Psychological adaptation, such as adopting an attitude of acceptance and adjustment, was also emphasised. Physical activity, often tailored to individual capabilities, was another preferred strategy. Despite those, a few young adults did not anticipate benefits from psychological adaptation, citing its limited effectiveness as subjectively perceived, and reported a tendency to avoid physical activity or exercise. On the other hand, “emotional and psychological support” emerged as another core subtheme for young adults when dealing with cognitive symptoms. Many participants expressed a need for validation from healthcare providers and sought treatments that addressed both the cognitive and emotional impacts of their symptoms, such as stress, frustration, anxiety, and feelings of isolation.

By contrast, for older adults, three subthemes were identified, including “non-pharmacological interventions”, “holistic expectations”, and “medication for cognitive symptom management”. Reliance on external support systems, including family support and social interaction, was a critical concept in their treatment preferences and expectations. Many older participants relied on their children or spouses to remind them of daily tasks, such as taking medications or preparing meals. Maintaining social engagement, whether through brief conversations with family members or neighbourhood walks, was considered vital for both cognitive stimulation and emotional well-being. Socialization was also seen as a remedy for the isolation often accompanying long COVID symptoms. Structured and predictable routines were also favoured, as they reduced cognitive load and minimised forgetfulness. These routines, such as placing essential items in visible locations, provided a sense of order and predictability, offering comfort in the face of cognitive challenges. Moreover, older adults expressed a preference and expectation for holistic treatment approaches that addressed not only cognitive symptoms but also physical health and psychological well-being. Another critical subtheme was the use of “medication for cognitive symptom management”, which included medications targeting cognitive symptoms directly and those addressing them indirectly. Like young adults, older adults highlighted the importance of sleep in cognitive recovery. Several participants noted improvements in memory and mental clarity following treatments aimed at enhancing sleep quality, which included both prescribed medications and traditional remedies.

Overall, although the treatment preferences and expectations of young and older adults in managing long COVID-associated cognitive symptoms differed markedly, both groups highlighted the importance of improving sleep and expressed a shared desire for more holistic, individualised care that addresses both cognitive and emotional well-being.

Theory for understanding how participants develop preferences and expectations

Using a constructivist grounded theory approach, we identified a central theory: “Individualised and Dynamic Adaptation to Cognitive Challenges”, which provides insights into participants’ preferences and expectations for managing long COVID cognitive symptoms and how they are formed. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the theory reflects how individuals, both young and older adults, navigate cognitive challenges through diverse, context-driven strategies influenced by personal, social, and systemic factors.

A theory of adapting to cognitive challenges in long COVID. This theoretical framework places individualised and dynamic adaptation at its centre, linking non-pharmacological approaches—such as practical tools, structured routines, physical activity, self-management of sleep, psychological adaptation, and external support—with pharmacological interventions that either directly address cognitive symptoms or indirectly support cognition (e.g. traditional Chinese medicine, sleep-enhancing medicines). A range of contextual factors—including age, severity of cognitive symptoms, economic affordability, accessibility of medical resources, prior management experiences, baseline health status, personal lifestyle, interests and attitudes, doctor–patient interactions, and health literacy—influence the selection and tailoring of these strategies. Collectively, these strategies contribute to participants’ holistic expectations across cognitive, physical, and psychological well-being, thereby shaping treatment preferences and expectations

Young adults in our study demonstrated a preference for non-pharmacological interventions to manage cognitive symptoms, while older adults tended towards a balanced approach combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies. Both groups emphasised the importance of addressing psychological well-being, although older adults also expressed concerns about physical symptoms, which some attributed to age-related health decline or overall physical condition. For example, a young participant stated, “But what I feel is that the older generation, and even society as a whole, don’t seem to care much about younger people dealing with symptoms like brain fog. So, I really hope that the mental health of young people like us, who are going through long COVID, can get the attention it truly deserves” (man, 20 s). An older participant shared, “I feel like it’s not just about the brain symptoms. I really hope the physical symptoms can improve as well. After all, as we get older, our overall health tends to decline, and many symptoms often occur together. So for someone like me, as an older adult, I just hope to achieve a full recovery for my body, and of course, that includes mental health too” (man, 70 s).

Beyond age, factors such as the severity of cognitive symptoms, economic affordability, accessibility of medical resources, prior management experiences, baseline health, personal lifestyle, interests, and attitude, doctor-patient interaction, and health literacy could influence participants’ preferences and expectations.

The subjectively perceived severity of cognitive symptoms emerged as a critical factor influencing their preferences and expectations. For young adults with mild-to-moderate symptoms, self-directed strategies (e.g. psychological adaptation and practical tools) were often perceived as effective. However, those with more severe cognitive impairments found such strategies less beneficial and expressed a potential need for medical interventions, especially when supported by clear communication from trusted healthcare providers. For instance, one participant shared, “I just can’t manage it on my own. I can’t remind myself no matter what I try. I’ve tried so many things, like using memos or setting alarms, but none of it works. I still forget, no matter what. I feel like I might need some medication to make it a bit better” (woman, 30 s). Another participant highlighted the importance of doctor-patient communication, stating, “I wish the doctor could explain what to expect and give more guidance instead of just prescribing pills. Otherwise, I don’t feel very comfortable taking it, as it doesn’t seem entirely reliable to me” (woman, 60 s). Additionally, while mild-to-moderate physical activities such as walking or light jogging improved mental clarity and reduced stress for some, others avoided exercise due to concerns about post-exertional fatigue. Medications, though generally avoided, were deemed acceptable for addressing intolerable symptoms like insomnia or anxiety, which exacerbated cognitive impairments. For example, “The doctor prescribed me something to help me sleep, and after a while, I noticed I could remember things a little better” (man, 60 s).

Participants’ prior management experiences and their corresponding perceived effectiveness was another key factor. Participants were more likely to trust and adopt strategies they had found effective in the past, while tending to avoid those that were ineffective and remaining cautious about treatments with uncertain outcomes. For example, a participant explained, “If I don’t sleep well, my memory is worse the next day.So I try to go to bed and wake up at the same fixed time every day, which helps a bit. I feel like I need to stick to this routine in the future because sleep is so important to me. It is not just about memory, as it might actually improve many aspects of my life” (woman, 30 s). An older adult participant highlighted the importance of continued family support, such as from children, “I feel happy when they show care and offer their support. In the future, I hope they can visit me more often, as they did before, or take the time to call or video chat with me. Having conversations and spending time together would mean a great deal to me. As older adults, this is often what we value and hope for the most” (woman 60 s). In contrast, another participant noted their reluctance to continue ineffective treatments: “I didn’t see a doctor about my memory issues, but I tried taking trying docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for a few months. It didn’t really help, so I stopped. And I don’t think I’ll take similar supplements in the future either, as they almost never seem to work” (woman, 30 s).

Economic affordability and accessibility of reliable medical resources also played significant roles. Several participants noted that potential financial limitations would affect their ability to pursue treatments, such as effective pharmacological options or professional therapies, when they become available. For example, one participant shared, “If there are new medications or treatment options in the future, it will depend on how expensive they are and how long the treatment will take. If it’s expensive and requires long-term treatment, it might be unaffordable. It also depends on how much the insurance can cover” (man, 70 s). Accessing reliable medical resources not only means whether the socioeconomic status of participants helps them access these resources, but also whether these resources are actually available. Many participants expressed frustration with the lack of clear guidelines and specialised clinics for managing long COVID cognitive symptoms in China. One participant remarked, “However, around here, there doesn’t seem to be any clear or formal approach to managing cognitive symptoms of long COVID. I haven’t heard of any specific places that specialize in treating this condition. It feels like no one really knows where to go for proper care” (woman, 70 s). In addition, stigma surrounding long COVID symptoms further compounded these challenges, particularly among younger adults. As one individual noted, “In real life, within my peer group, cognitive symptoms, especially those that are often subjective or less obvious, such as brain fog and mental fatigue, are frequently seen as exaggerated or even fabricated. I feel that cultural attitudes in China reinforce this bias, viewing prolonged recovery as a lack of personal effort or adaptability. This certainly adds a psychological burden to our group on top of the physical challenges of long COVID”, “People think you’re exaggerating or being lazy. It’s hard to talk about it without being judged” (man, 20 s).

Personal lifestyles choices, interests, and attitudes also influenced treatment preferences and expectations. For instance, although some participants tended to avoid exercise due to concerns about post-exertional fatigue, another potential reason could be a lack of interest in physical exercise. “I didn’t have a habit of exercising before (the COVID-19 pandemic), and I’m also worried that exercising might worsen my fatigue symptoms” (woman, 30 s). Baseline health conditions further shaped decisions, with participants managing multiple health issues tending to prioritize low-risk, non-invasive treatments. Finally, personal health literacy was also a crucial factor. We found that participants with higher health literacy, as reflected in their ability to critically assess potential treatment risks and benefits (based on our observations during interviews), were better equipped to understand and evaluate potential treatment options, further strengthening the rationale behind their treatment preferences and expectations.

link