The proposed EU Directives for AI liability leave worrying gaps likely to impact medical AI

The newly proposed EU Directives—PLD and AILD—will likely fall short of providing a clear and uniform path to liability for some patients who are injured by some black-box medical AI systems. This is because patients may not be successful in lawsuits against either healthcare providers or manufacturers under national law, even with the newly proposed Directives. With regard to manufacturers, some black-box medical AI systems may (1) not be considered defective products subject to strict product liability under national law even with the proposed PLD’s rules and (2) cause an injury that cannot be connected to manufacturer fault subject to fault-based liability under national law even with the proposed AILD’s rules.

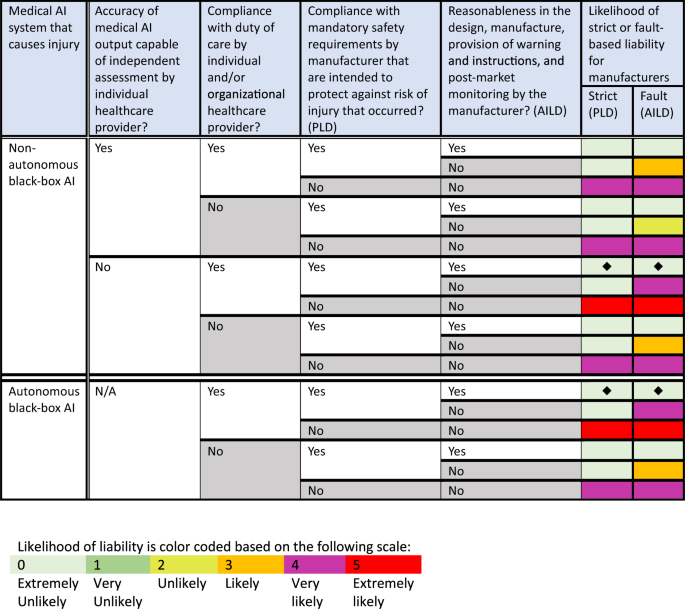

Figure 1 illustrates the likelihood of a successful lawsuit against manufacturers for patient injuries caused by some black-box medical AI systems under national law with the proposed PLD and AILD.

Analysis of likelihood of potential liability for manufacturers of black-box medical AI systems that can cause injury (rows) based on variables related to the AI system’s features, use, and development (columns). Likelihood of liability is color coded based on the following scale: Light green box (0) = Extremely unlikely. Medium green box (1) = Very unlikely. Lime green box (2) = Unlikely. Orange box (3) = Likely. Purple box (4) = Very likely. Red box (5) = Extremely likely. Black diamonds represent gaps in liability when compared with likelihood of liability as shown in Fig. 2. AI artificial intelligence, PLD proposed Product Liability Directive, AILD proposed AI Liability Directive.

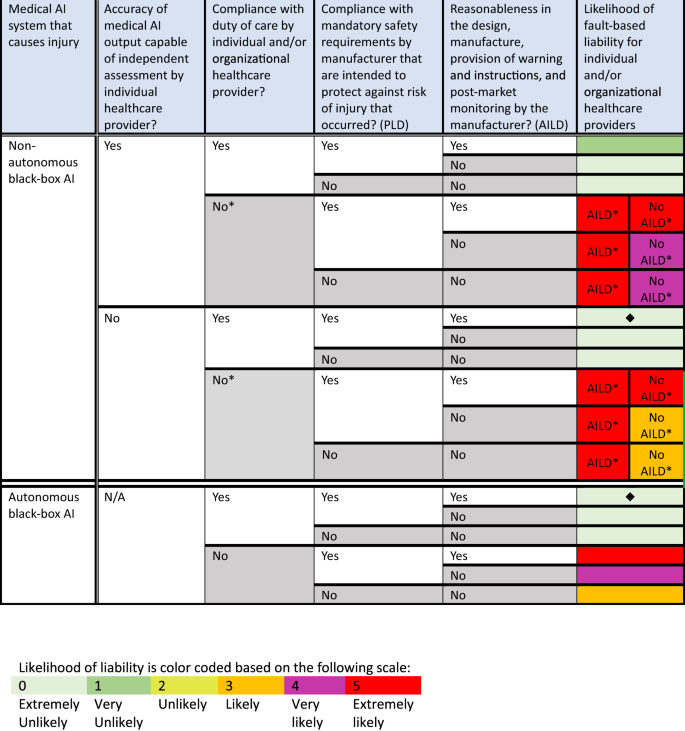

With regard to healthcare providers, some black-box medical AI systems may cause an injury that also cannot be connected to the fault of either an individual or organizational healthcare provider under national law, even with the proposed AILD. Figure 2 illustrates the likelihood of a successful lawsuit against healthcare providers for patient injuries caused by some black-box medical AI systems under national law with the proposed PLD and AILD.

Analysis of likelihood of potential liability for individual and organizational healthcare providers that use black-box medical AI systems that can cause injury (rows) based on variables related to the AI system’s features, use, and development (columns). Likelihood of liability is color coded based on the following scale: Light green box (0) = Extremely unlikely. Medium green box (1) = Very unlikely. Lime green box (2) = Unlikely. Orange box (3) = Likely. Purple box (4) = Very likely. Red box (5) = Extremely likely. Black diamonds represent gaps in liability when compared with likelihood of liability as shown in Fig. 1. The asterisk means that the AILD seems likely to aim to cover claims for damages if the non-compliance by the healthcare provider occurred prior to the AI output or failure to produce the AI output. However, the AILD does not appear to aim to cover claims for damages if the non-compliance by the healthcare provider occurred subsequent to the AI output (see AILD, Recital (15)). AI artificial intelligence, PLD proposed Product Liability Directive, AILD proposed AI Liability Directive.

As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, there are two scenarios in which a patient’s lawsuit for an AI-caused injury against both manufacturers and healthcare providers is extremely unlikely to succeed. These scenarios, further explained in Supplementary Scenarios 1 and 2, possibly occur when (1) a non-autonomous black-box AI produces an output, which physicians review and rely upon but cannot independently assess because they cannot understand the AI’s algorithmic reasoning process (Supplementary Scenario 1), and (2) an autonomous black-box AI makes medical decisions not subject to independent physician review and assessment (Supplementary Scenario 2). As a result, these two scenarios demonstrate potential liability gaps for AI-caused patient injuries under national law, which are still not filled by the proposed PLD and AILD.

First, a patient in the EU who suffers an injury in either of the two supplementary scenarios is unlikely to succeed in a lawsuit against the manufacturer based on a defective product. The EC has already recognized that AI systems “with self-learning capabilities also raise the question of whether unpredictable deviations in the decision-making path can be treated as defects”12. Assume that in both scenarios, the hypothetical black-box AI systems have obtained an EU CE mark to certify that they have “been assessed by the manufacturer and deemed to meet EU safety, health and environmental protection requirements”13. If we further assume that the manufacturer complied with mandatory safety requirements (PLD, Art. 6(1)(f)) and that patients were properly informed that the AI was being used in their care and the conditions and risks associated with its use (see PLD, Art. 6(1)(h)), these black-box medical AI systems may not be considered defective products subject to strict liability for manufacturers under national law because the AI’s noninterpretable reasoning process may be deemed outside of the manufacturer’s control (PLD, Art. 6(1)(e))1.

We note that although some EU Member States may impose strict liability for “dangerous activity” outside of national product liability law, according to the EC, such liability “for the operation of computers, software or the like is so far widely unknown in Europe” and thus does not provide a clear path for recovery by patients who are injured by the black-box medical AI systems discussed here12.

Second, a patient in the EU who suffers an injury in either of the two scenarios is also unlikely to succeed in a lawsuit based on the fault of the manufacturer or the individual/organizational healthcare provider because the patient may not be able to identify a breach of a duty of care by any party. Notably, the AILD does not create any new substantive duties of care for manufacturers or individual/organizational healthcare providers, but rather relies on existing “dut[ies] of care under Union or national law” to govern “fault” (see AILD, Explanatory Memorandum and Recital (23))2. Generally, a party breaches their duty of care under national law if they fail to act reasonably under the circumstances (or fail to comply with the standard of care)12. The AILD’s reliance on existing duties of care to assess fault is problematic because, as the EC previously observed, “[t]he processes running in AI systems cannot all be measured according to duties of care designed for human conduct” making it difficult to determine fault12.

Patients injured by black-box AI systems may have trouble succeeding in lawsuits based on the fault of manufacturers or healthcare providers because, according to the EC, “[e]merging digital technologies make it difficult to apply fault-based liability rules, due to the lack of well established models of proper functioning of these technologies and the possibility of their developing as a result of learning without direct human control”12. For example, a manufacturer may not be at fault if the patient’s injury is not caused by the manufacturer’s design of a black-box AI system, but rather by “subsequent choices made by the AI technology independently”12. Similarly, assuming that the mere use of an EU CE-marked black-box AI system does not breach a duty of care, individual/organizational healthcare providers may not be at fault for AI-caused damage if the providers lack both control over the AI’s learning and reasoning processes and the ability to independently assess the accuracy of the AI’s output. As a result, if neither the manufacturer nor the healthcare provider is likely to face liability for AI-caused damage, as demonstrated in Supplementary Scenarios 1 and 2, under national law, even with the newly proposed Directives, two potential liability gaps emerge.

To further illustrate how these potential gaps might manifest in practice, we present a hypothetical example of each type of system. The first type is a non-autonomous black-box AI that predicts the origin of metastatic cancer of unknown primary (CUP) by “utilis[ing] [a] large number of genomic and transcriptomic features”14. As cancer origin “can be a significant indicator of how the cancer will behave clinically,” a human physician might rely on the AI’s prediction to develop a treatment plan14. The second type is an autonomous black-box AI that uses a deep learning algorithm to evaluate X-rays without the input of a radiologist15. This AI can generate final radiology reports for X-rays that reveal no abnormalities, while those with suspected abnormalities will be referred to a human radiologist for final evaluation and reporting15.

Assume that in both hypotheticals, in addition to complying with all safety requirements and obtaining an EU CE marking, the black-box AI systems are functioning as designed by the manufacturer (i.e., to make decisions and recommendations using noninterpretable complex algorithmic reasoning), their design was reasonable under the circumstances, and the manufacturer was reasonable in providing warnings, instructions, and post-market monitoring. In this case, the injured patient is not likely to be successful in a lawsuit against the manufacturer based on either a product defect or manufacturer fault. Additionally, if the healthcare organizations and individual providers involved also complied with their duties of care associated with using the hypothetical black-box AI systems, for example through the reasonable selection and implementation of the AI system in clinical practice, the patient is not likely to be successful in a lawsuit against the healthcare providers based on provider fault.

As shown in Supplementary Scenario 1, Potential Liability Gap 1 will manifest for the first hypothetical black-box system when the non-autonomous AI provides an incorrect CUP prediction that causes a patient injury. This liability gap occurs because while a human physician oversaw and relied upon the AI’s prediction to maximize the patient’s chance for successful treatment, they could not independently assess the accuracy of the AI’s output. As a result, the physician’s reliance on the output of a system used in accordance with its EU CE marking will likely not violate an applicable duty of care for the physician who could not have known that the AI’s prediction was incorrect. This gap in liability is remarkable because the AI is making a medical recommendation that would have otherwise been made by a human physician, who the patient could have sued for fault (or medical malpractice). For example, had a human pathologist misclassified the CUP, the patient would likely succeed in a lawsuit against the human pathologist if their misclassification violated the standard of care or medical lege artis. However, this path to liability becomes unavailable under national law even with the proposed AILD when a non-autonomous black-box AI, rather than a human pathologist, predicts the CUP origin, undermining the EC’s goal of providing the same level of protection for victims of AI-caused damage.

As shown in Supplementary Scenario 2, Potential Liability Gap 2 will manifest for the second hypothetical black-box AI system when the autonomous AI reports no abnormality for an X-ray film with remarkable findings, which leads to a missed diagnosis and patient injury. This gap in liability is remarkable because the AI is making a medical decision that would have otherwise been made by a human physician, who the patient could have sued for fault (or medical malpractice). For example, if a human radiologist missed an abnormality in the X-ray film, the patient would likely succeed in a lawsuit against the radiologist if the missed abnormality violated the standard of care or medical lege artis. However, this path to liability becomes unavailable under national law even with the proposed AILD when an autonomous black-box AI, rather than a human radiologist, evaluates the X-ray, thus again undermining the EC’s goal of providing the same level of protection for victims of AI-caused damage.

link